Find free online Chemistry Topics covering a broad range of concepts from research institutes around the world.

Measurement of ΔU and ΔH Using Calorimetry

Calorimeter is used for measuring the amount of heat change in a chemical or physical change. In calorimetry, the temperature change in the process is measured which is inversely proportional to the heat change. By using the expression C = q/mΔT, we can calculate the amount of heat change in the process. Calorimetric measurements are made under two different conditions.

- At constant volume (qV)

- At constant pressure (qP)

(A) ΔU Measurements

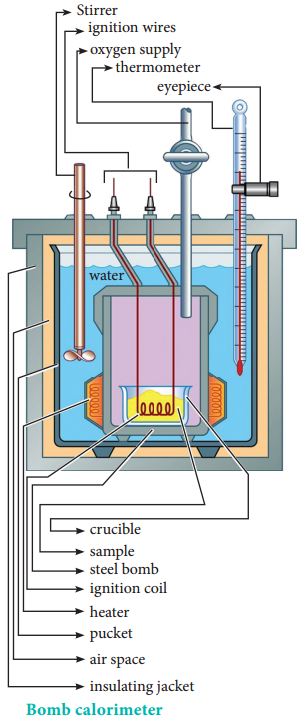

For chemical reactions, heat evolved at constant volume, is measured in a bomb calorimeter.

The inner vessel (the bomb) and its cover are made of strong steel. The cover is fitted tightly to the vessel by means of metal lid and screws.

A weighed amount of the substance is taken in a platinum cup connected with electrical wires for striking an arc instantly to kindle combustion. The bomb is then tightly closed and pressurized with excess oxygen. The bomb is immersed in water, in the inner volume of the calorimeter.

A stirrer is placed in the space between the wall of the calorimeter and the bomb, so that water can be stirred, uniformly. The reaction is started by striking the substance through electrical heating.

A known amount of combustible substance is burnt in oxygen in the bomb. Heat evolved during the reaction is absorbed by the calorimeter as well as the water in which the bomb is immersed. The change in temperature is measured using a Beckman thermometer. Since the bomb is sealed its volume does not change and hence the heat measurements is equal to the heat of combustion at a constant volume (ΔUc°).

The amount of heat produced in the reaction (ΔUc°) is equal to the sum of the heat abosrbed by the calorimeter and water.

Heat absorbed by the calorimeter

q1 = k.∆T

where k is a calorimeter constant equal to mcCc (mc is mass of the calorimeter and Cc is heat capacity of calorimeter)

Heat absorbed by the water

q2 = mwCwΔT

where mw is molar mass of water

Cw is molar heat capacity of water (75.29 J K-1 mol-1)

Therefore ΔUc = q1 + q2

= k.ΔT + mw Cw ΔT

= (k + mwCw) ΔT

Calorimeter constant can be determined by burning a known mass of standard sample (benzoic acid) for which the heat of combustion is known (- 3227 kJmol-1)

The enthalpy of combustion at constant pressure of the substance is calculated from the equation (7.17)

ΔHC°(Pressure) = ΔU°(Vol) + ΔngRT

Applications of Bomb Calorimeter:

- Bomb calorimeter is used to determine the amount of heat released in combustion reaction.

- It is used to determine the calorific value of food.

- Bomb calorimeter is used in many industries such as metabolic study, food processing, explosive testing etc.

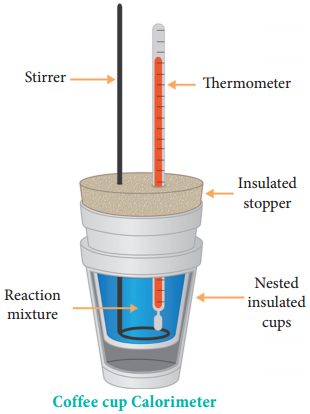

(b) ΔH Measurements

Heat change at constant pressure (at atmospheric pressure) can be measured using a coffee cup calorimeter. A schematic representation of a coffee cup calorimeter is given in Figure 7.7. Instead of bomb, a styrofoam cup is used in this calorimeter. It acts as good adiabatic wall and doesn’t allow transfer of heat produced during the reaction to its surrounding.

This entire heat energy is absorbed by the water inside the cup. This method can be used for the reactions where there is no appreciable change in volume. The change in the temperature of water is measured and used to calculate the amount of heat that has been absorbed or evolved in the reaction using the following expression.

q = mwCwΔT

where mw is the molar mass of water and Cw is the molar heat capacity of water (75.29 J K-1 mol-1)

Problem 7. 4

Calculate the enthalpy of combustion of ethylene at 300 K at constant pressure, if its heat of combustion at constant volume (ΔU) is – 1406 kJ.

The complete ethylene combustion reaction can be written as,

C2H4 (g) + 3O2 (g) → 2CO2 (g) + 2H2O(l)

ΔU = – 1406 kJ

Δn = nP(g) – nr(g)

Δn = 2 – 4 = -2

ΔH = ΔU + RTΔng

ΔH = – 1406 + (8.314 × 10-3 × 300 × (-2)

ΔH = – 1410.9 kJ

Applications of the Heat of Combustion:

(1) Calculation of Heat of Formation:

Since the heat of combustion of organic compounds can be determined with considerable ease, they are employed to calculate the heat of formation of other compounds.

For example let us calculate the standard enthalpy of formation ΔHf° of CH4 from the values of enthalpy of combustion for H2, C(graphite) and CH4 which are – 285.8, – 393.5, and -890.4 kJ mol-1 respectively.

Let us interpret the information about enthalpy of formation by writing out the equations. It is important to note that the standard enthalpy of formation of pure elemental gases and elements is assumed to be zero under standard conditions. Thermochemical equation for the formation of methane from its constituent elements is,

C(graphite) + 2H2(g) → CH4(g)

ΔHf° = X kJ mol-1 ………….. (1)

Thermo chemical equations for the combustion of given substances are,

H2(g) + \(\frac{1}{2}\)O2 → H2O(l)

ΔH° = – 258.8 kJ mol-1 ……………… (2)

C(graphite) + O2 → CO2

ΔH° = – 393.5 kJ mol-1 ……………… (3)

CH4(g) + 2O2 → CO2(g) + 2H2O(l)

ΔH° = – 890.4 kJ mol-1 ……………… (4)

Since methane is in the product side of the required equation (i), we have to reverse the equation (iv)

CO2(g) + 2 H2O (l) → CH4(g) + 2 O2

ΔH° = + 890.4 kJ mol-1 ……………… (5)

In order to get equation (i) from the remaining,

(i) = [(ii) × 2] + (iii) + (v)

X = [(- 285.8) × 2] + [- 393.5] + [+ 890.4]

= – 74.7 kJ

Hence, the amount of energy required for the formation of 1 mole of methane is – 74.7 kJ

The heat of formation methane = – 74.7 kJ mol-1

Calculation of Calorific Value of Food and Fuels:

The calorific value is defined as the amount of heat produced in calories (or joules) when one gram of the substance is completely burnt. The SI unit of calorific value is J kg-1. However, it is usually expressed in cal g-1.

Heat of Solution:

Heat changes are usually observed when a substance is dissolved in a solvent. The heat of solution is defined as the change in enthalpy when one mole of a substance is dissolved in a specified quantity of solvent at a given temperature.

Heat of Neutralisation:

The heat of neutralisation is defined as “The change in enthalpy when one gram equivalent of an acid is completely neutralised by one gram equivalent of a base or vice versa in dilute solution”.

HCl(aq) + NaOH(aq) → NaCl (aq) + H2O(l); ΔH = – 57.32 kJ

H+(aq) + OH–(aq) → H2O(l); ΔH = – 57.32 kJ

The heat of neutralisation of a strong acid and strong base is around – 57.32 kJ, irrespective of nature of acid or base used which is evident from the below mentioned examples.

HCl (aq) + KOH(aq) → KCl (aq) + H2O(l)

ΔH = – 57.32 kJ

HNO3(aq) + KOH(aq) → KNO3(aq) + H2O(l)

ΔH = – 57.32 kJ

H2SO4(aq) + 2KOH(aq) → K2SO4(aq) + 2 H2O(l)

ΔH = – 57.32 kJ × 2

The reason for this can be explained on the basis of Arrhenius theory of acids and bases which states that strong acids and strong bases completely ionise in aqueous solution to produce H+ and OH– ions respectively. Therefore in all the above mentioned reactions the neutralisation can be expressed as follows.

H+(aq) + OH–(aq) → H2O(l); ΔH = – 57.32 kJ

Molar Heat of Fusion

The molar heat of fusion is defined as “the change in enthalpy when one mole of a solid substance is converted into the liquid state at its melting point”. For example, the heat of fusion of ice can be represented as

![]()

Molar Heat of Vapourisation

The molar heat of vaporisation is defined as “the change in enthalpy when one mole of liquid is converted into vapour state at its boiling point”. For example, heat of vapourisation of water can be represented as

![]()

Molar Heat of Sublimation

Sublimation is a process when a solid changes directly into its vapour state without changing into liquid state. Molar heat of sublimation is defined as “the change in enthalpy when one mole of a solid is directly converted into the vapour state at its sublimation temperature”. For example, the heat of sublimation of iodine is represented as

![]()

Another example of sublimation process is solid CO2 to gas at atmospheric pressure at very low temperatures.

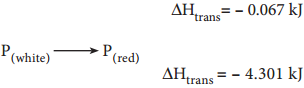

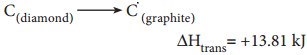

Heat of Transition

The heat of transition is defined as “The change in enthalpy when one mole of an element changes from one of its allotropic form to another. For example, the transition of diamond into graphite may be represented as

Similarly the allotropic transitions in sulphur and phosphorous can be represented as follows,

![]()